Architecture has always served as a canvas for power. Throughout history, rulers and religious leaders have wielded spatial design as a tool to communicate dominance, establish social hierarchies, and shape collective consciousness.

From the towering ziggurats of ancient Mesopotamia to the elaborate processional ways of imperial capitals, built environments have functioned as three-dimensional manifestations of authority. These structures don’t merely house functions—they perform ideological work, inscribing power relationships into the very fabric of urban space.

🏛️ The Architecture of Authority: How Space Communicates Power

Spatial hierarchy operates through a sophisticated visual language that transcends words. When we encounter monumental architecture, our bodies respond instinctively to scale, proportion, and positioning. A towering facade forces us to crane our necks upward, physically enacting submission. A long processional axis requires sustained movement toward a distant focal point, transforming approach into ritual.

The semiotics of dominance in design manifests through several key strategies. Verticality establishes supremacy—the tallest structure commands the skyline and visual attention. Centrality claims importance—positioning at urban cores or geographic centers asserts primacy. Axiality creates directionality—long sight lines channel movement and focus toward seats of power.

These design principles operate across cultures and epochs because they tap into fundamental human spatial cognition. We navigate the world through hierarchical mental maps, and architectural designers have long understood how to manipulate these cognitive frameworks to reinforce social structures.

Sacred Mountains: Temples as Cosmic Hierarchies

Religious architecture represents perhaps the most explicit fusion of spatial hierarchy and ideological dominance. Temples across civilizations have employed vertical organization to mirror cosmic orders, with earthly realms at ground level and divine spaces elevated above.

The Ziggurat Model: Babylon’s Stairway to Heaven

Mesopotamian ziggurats exemplify architectural dominance through staged ascension. These massive stepped pyramids rose from flat floodplains, visible for miles across the landscape. The Great Ziggurat of Ur, constructed around 2100 BCE, featured three terraced levels ascending to a temple shrine dedicated to the moon god Nanna.

Access to upper levels was strictly controlled, with only priests permitted to climb the ceremonial staircases. This vertical segregation physically enacted social hierarchy—common people occupied the base, priests ascended to intermediate levels, and the pinnacle remained the exclusive domain of divine-human interface. The ziggurat’s form made power visible and legible across the entire city-state.

Hindu Temple Cosmology: The Mountain at the Center of the World

Hindu temple architecture developed an elaborate spatial theology based on Mount Meru, the sacred mountain at the center of the universe. Temple complexes like Angkor Wat in Cambodia translate this cosmic geography into built form through concentric enclosures and vertical towers (shikhara).

The spatial progression from outer courtyards to inner sanctum (garbhagriha) mirrors the journey from mundane to sacred. Each successive threshold requires greater ritual purity, effectively filtering visitors according to social and religious status. The towering central spire symbolizes the axis mundi—the cosmic axis connecting earthly and celestial realms—with the ruling class claiming proximity to this sacred center.

Gothic Cathedrals: Vertical Transcendence in Stone

Medieval European cathedrals pushed verticality to unprecedented heights, using technological innovations like pointed arches and flying buttresses to achieve soaring nave spaces. These structures dominated their urban contexts both physically and symbolically, serving as permanent reminders of ecclesiastical authority.

The vertical emphasis of Gothic architecture directed human attention—and aspiration—upward toward heaven. This spatial rhetoric reinforced Church teachings about the hierarchical ordering of creation, with God at the apex, Church authorities as earthly intermediaries, and laypeople at the base. The architectural experience itself became a form of theological instruction.

🏰 Palatial Power: Royal Residences as Political Theaters

While temples mediate relationships between humans and the divine, palaces establish the primacy of rulers over subjects. Palatial architecture creates carefully choreographed environments where power is displayed, performed, and naturalized through spatial arrangements.

The Forbidden City: Concentric Authority

Beijing’s Forbidden City represents one of history’s most elaborate expressions of spatial hierarchy. Constructed between 1406 and 1420, this vast palace complex encompasses 980 buildings arranged along a central north-south axis. The entire layout embodies Confucian cosmology and political philosophy.

Access zones radiated outward from the emperor’s innermost chambers in concentric rings of decreasing sanctity. The Outer Court housed governmental functions accessible to officials, while the Inner Court remained reserved for the imperial family. This spatial segregation materialized the concept of the emperor as the “Son of Heaven”—a sacred figure whose very person required physical separation from ordinary mortals.

The architecture enforced protocols through design. Progressive gates and courtyards required repeated acts of entrance, each threshold reinforcing the visitor’s subordinate status. The emperor’s throne in the Hall of Supreme Harmony sat elevated on a platform within a platform within a platform—a triple assertion of hierarchical superiority.

Versailles: Absolutism in Spatial Form

Louis XIV’s palace at Versailles transformed the royal residence into a comprehensive statement of absolutist power. The palace, gardens, and town were conceived as an integrated whole, with geometric precision radiating from the king’s bedchamber at the compositional center.

The famous Hall of Mirrors functioned as both architectural space and political theater. This 73-meter gallery, adorned with 357 mirrors, hosted ceremonies and diplomatic receptions where foreign envoys walked the length of the hall under French royal portraits, culminating in audience with the Sun King himself. The spatial sequence was designed to overwhelm and subordinate.

The gardens extended palatial control into the landscape through radical geometry. Nature itself was disciplined into parterres, fountains, and sight lines converging on the palace. This transformation of wilderness into ordered space metaphorically demonstrated the king’s power to impose rational order on chaos—a core justification for absolute monarchy.

Processional Axes: Choreographing Movement and Meaning

Processional ways represent power extended into urban space. These monumental corridors channel movement, stage spectacles of authority, and structure collective experience of the city according to hierarchical principles.

Ancient Babylon’s Processional Way

The Processional Way of ancient Babylon connected the Ishtar Gate to the city’s ceremonial center, creating a stage for religious festivals and royal processions. Walls lined with glazed brick reliefs depicting lions and dragons flanked the route, transforming the walk into an immersive experience of divine and royal iconography.

During the annual New Year festival, the king led a procession along this route, publicly enacting his role as intermediary between gods and people. The architecture framed and amplified this performance, providing an appropriately magnificent backdrop for displays of power.

Nazi Berlin and Mussolini’s Rome: Fascist Axes

Twentieth-century totalitarian regimes recognized architecture’s capacity to legitimate authority through spatial organization. Hitler’s architect Albert Speer designed the never-completed Welthauptstadt Germania, featuring a north-south axis 5 kilometers long terminated by a massive domed Volkshalle capable of holding 180,000 people.

Mussolini’s Via dell’Impero in Rome cut through ancient neighborhoods to create a processional route connecting the Colosseum to Piazza Venezia. This axis literally and symbolically connected Fascist rule to the glories of imperial Rome, using spatial continuity to claim historical legitimacy.

Both projects demonstrate how processional axes concentrate attention, choreograph movement, and create frameworks for mass spectacles that dissolve individual identity into collective experience—a key mechanism of totalitarian power.

Washington’s National Mall: Democratic Monumentality

Not all processional axes serve authoritarian ends. Washington D.C.’s National Mall creates a monumental axis anchored by the Capitol and Lincoln Memorial, with the Washington Monument marking the center. This spatial organization embodies democratic republican ideals—power dispersed across branches of government rather than concentrated in a single ruler.

The Mall functions as a space of public gathering and protest, hosting everything from presidential inaugurations to civil rights marches. Its openness and accessibility distinguish it from the exclusive palatial axes of absolute monarchies, though it still employs monumental scale to communicate state authority and national identity.

⚖️ Reading the Landscape: Decoding Spatial Hierarchy in Contemporary Cities

Understanding historical precedents illuminates contemporary urban landscapes. Modern cities continue to encode power relationships through architectural and spatial strategies, though often in less explicit forms than ancient temples or royal palaces.

Corporate headquarters employ many classical techniques—verticality through skyscrapers, centrality through prime urban locations, controlled access through security protocols. The corporate tower functions as a contemporary palace, with executive suites occupying the most elevated and exclusive spaces.

Government buildings maintain traditions of monumental architecture. Capitol buildings, supreme courts, and presidential residences use classical vocabularies of columns, domes, and symmetry to communicate authority and permanence. These design choices aren’t arbitrary—they deliberately invoke associations with historical seats of power.

Exclusionary Architectures

Contemporary spatial hierarchy also operates through more subtle mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion. Gated communities create residential enclaves separated from surrounding urban fabric. Shopping malls and corporate plazas occupy private property but mimic public space, allowing owners to control access and behavior.

Even seemingly innocuous design elements can enforce hierarchies. Hostile architecture—benches with armrests dividing seating areas, spikes under bridges, aggressively angled surfaces—targets homeless populations, using design to exclude unwanted bodies from public space. These interventions reveal how spatial control remains a fundamental tool of power.

🌍 Cultural Variations in Hierarchical Expression

While patterns of architectural dominance appear across civilizations, cultural contexts shape specific expressions. Comparing approaches reveals how different societies understand and legitimate authority.

East Asian palace architecture often emphasizes horizontal extension rather than vertical assertion. The Forbidden City sprawls across 72 hectares, using expansive courtyards and sequential gateways rather than soaring heights. This horizontal hierarchy reflects philosophical traditions emphasizing harmony and interconnection within cosmic order.

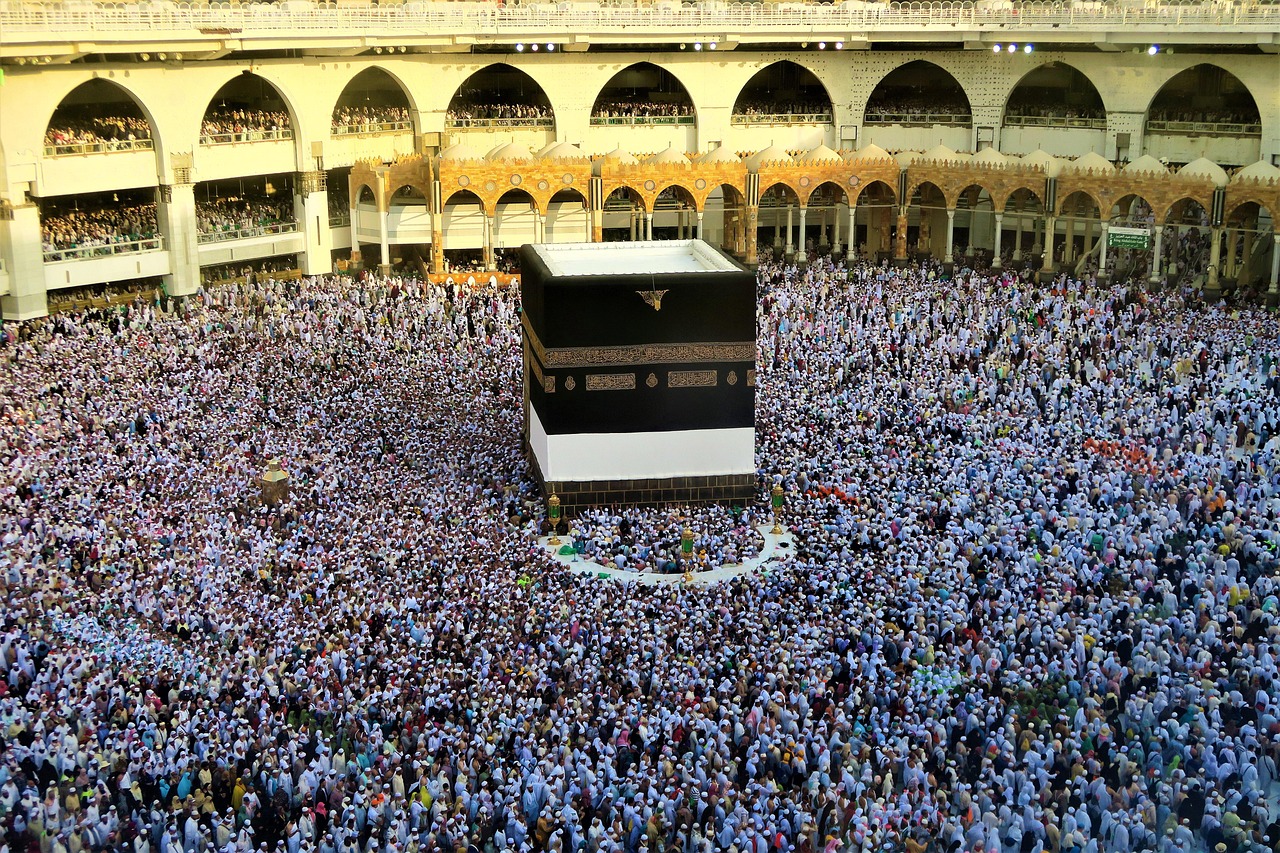

Islamic architecture developed distinctive approaches to expressing hierarchy while navigating theological prohibitions on representational imagery and concerns about competing with divine majesty. Mosques employ domes, minarets, and elaborate geometric ornament, but often maintain more human scale than Christian cathedrals. The emphasis shifts from vertical transcendence to horizontal congregation and geometric perfection as manifestations of divine order.

Indigenous American societies created monumental centers like Teotihuacan and Cahokia that employed processional axes and pyramidal structures, demonstrating that hierarchical spatial organization isn’t unique to Old World civilizations. The Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan rises 65 meters, dominating the cityscape and channeling ceremonial processions along the Avenue of the Dead.

Resistance and Alternative Spatial Practices

Architecture’s capacity to communicate dominance has also inspired counter-practices seeking to create more egalitarian spatial relationships. Various movements have challenged hierarchical design traditions.

Modernist architecture initially embraced utopian visions of social transformation through design. Figures like Le Corbusier advocated for radically new spatial organizations that would dissolve class hierarchies. However, many modernist projects ultimately reproduced hierarchical relationships through different formal vocabularies—the tower-in-the-park typology creating elevated structures separated from ground-level public space.

Participatory design movements seek to democratize the design process itself, involving community members in shaping their built environments rather than imposing top-down plans. This approach challenges not just formal hierarchies but the power relationships embedded in design practice.

Temporary interventions and tactical urbanism create alternative uses for urban space, appropriating environments designed for one purpose to serve different needs. Street festivals, pop-up parks, and protest occupations demonstrate how spatial meaning can be contested and renegotiated.

🔮 The Future of Spatial Hierarchy

As societies evolve, so do spatial expressions of power and hierarchy. Contemporary trends suggest both continuities and transformations in how architecture communicates dominance.

Digital technologies introduce new dimensions to spatial hierarchy. Virtual environments create spaces without physical constraints, yet often reproduce familiar hierarchical structures—exclusive access, premium zones, elevated positions for privileged users. The metaverse may simply relocate rather than eliminate spatial hierarchies.

Climate change and resource constraints challenge monumental building traditions. Sustainable design prioritizes efficiency and adaptation rather than permanence and monumentality. This shift could enable more flexible, less hierarchical spatial organizations—or simply create new hierarchies based on access to climate-resilient infrastructure.

Increasing awareness of historical injustices embodied in built environments drives efforts to reckon with problematic monuments and spaces. Removing Confederate statues, renaming buildings, and reinterpreting heritage sites acknowledge that architecture carries ideological weight. These debates reflect ongoing struggles over who controls public space and whose histories are commemorated.

Lessons from Spatial Hierarchies

Studying temples, palaces, and processional axes reveals architecture’s profound capacity to shape social relationships. These structures don’t merely reflect existing hierarchies—they actively produce and maintain them by naturalizing power relationships through spatial experience.

Understanding these mechanisms enables critical engagement with contemporary environments. Every building, plaza, and street embeds assumptions about power, access, and belonging. Recognizing spatial hierarchy as a constructed rather than natural condition opens possibilities for creating more equitable environments.

The designers who created Versailles, the Forbidden City, and Babylon’s Processional Way understood what contemporary architects and urbanists must rediscover: space shapes experience, experience shapes consciousness, and consciousness shapes society. The question remains whether this knowledge will serve to reproduce hierarchies or to imagine alternatives. Architecture’s power can manifest as dominance or as liberation—the choice lies with those who design and those who inhabit the spaces we build. 🌆

Toni Santos is a cultural storyteller and researcher devoted to exploring the hidden narratives of sacred architecture, urban planning, and ritual landscapes. With a focus on temples aligned with celestial events, sacred cities, and symbolic structures, Toni investigates how ancient societies designed spaces that were not merely functional, but imbued with spiritual meaning, social identity, and cosmic significance. Fascinated by ritual spaces, energy lines, and the planning of sacred cities, Toni’s journey takes him through temples, ceremonial precincts, and urban designs that guided communal life and connected people to the cosmos. Each story he tells reflects the profound ways in which sacred geography shaped cultural beliefs, seasonal cycles, and spiritual practice. Blending archaeoastronomy, cultural anthropology, and historical storytelling, Toni researches the orientation, symbolism, and ritual functions of temples and urban layouts — uncovering how sacred architecture and geography reveal complex layers of cosmology, belief, and social organization. His work honors the temples, monuments, and ceremonial spaces where tradition and sacred knowledge were encoded, often beyond written history. His work is a tribute to: Temples aligned with celestial events and the rhythms of the cosmos The design and planning of sacred cities as reflections of cultural and spiritual order Symbolic structures and ritual spaces that conveyed meaning across generations Energy lines and sacred geography that connected people, land, and sky Whether you are passionate about sacred architecture, intrigued by ritual urban planning, or drawn to the symbolic power of space, Toni invites you on a journey through temples, cities, and landscapes — one structure, one ritual, one story at a time.